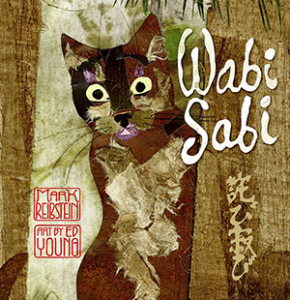

Recently I came upon the extraordinary picture book, Wabi Sabi, by Mark Reibstein and Ed Young. I had heard of the Japanese phrase “wabi sabi,” but I never really understood what it meant until I read this story.

Author Mark Reibstein explains “wabi sabi” this way:

Wabi sabi is a way of seeing the world that is at the heart of Japanese culture. It finds beauty and harmony in what is simple, imperfect, natural, modest, and mysterious. It can be a little dark, but it is also warm and comfortable. It may best be understood as a feeling, rather than as an idea.

The preface helps, but like the cat named Wabi Sabi in the story, I have to go on a journey with her to find what “wabi sabi” really means.

The first extraordinary experience I encounter reading Wabi Sabi, is the immediacy of the Japanese world. The book opens vertically, as if I were reading traditional Japanese. In the same moment, I’m introduced to Ed Young’s gorgeous and mysterious mixed media illustrations created from “wabi sabi” lost and found imperfect objects.

On the story’s first page, strangers meet Wabi Sabi the cat and ask what “wabi sabi” means. The owner draws in a breath through her teeth and says, “That’s hard to explain.” As the cat owner pauses, my eyes slide to the bottom of the page and find poetry, one in Japanese, one in English:

The cat’s tail twitching

She watches her master, still

waiting in silence.

And in that silence, Wabi Sabi the cat begins an adventure to find the meaning of her name—and I go along with the same curiosity. The wise, old monkey is somewhere in the forest, the story says. He can explain.

The cat and I find the wise, old monkey making tea. “What’s wabi sabi?” the cat asks.

The old monkey’s haiku reply is confusing:

The pale moon resting

on foggy water. Hear that

splash? A frog’s jumped in.

The cat is mystified, and so am I. The monkey continues.

Listen. Watch. Feel … He moved slowly but gracefully,

as if he were dancing, and he handled his things as if they were gold,

although they were wooden or clay.

Wabi Sabi looks around afresh and sees her world in haiku,

alive and dying

too, like the damp autumn leaves

curled beneath their feet.

Taking a cue from the cat, I look around at my surroundings through a “wabi sabi” sort of lens. I stop, listen, look, feel. The weather can change quickly here in Minnesota. Fall’s dried leaves still cling to branches, though it is bitter cold outside. Dark branches stretch against blue sky. Snow piles on roof tops. A long-fingered icicle drips outside my window. Wabi sabi?

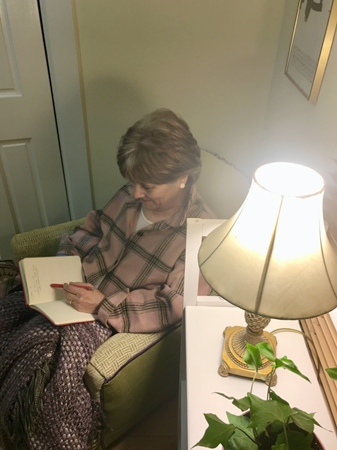

An overstuffed reading chair. A hand-me-down blanket. An old lamp. Wabi sabi?

With each glance and reflection, I feel calmer, more patient, more appreciative in a wabi sabi sort of way of uneven edges, scratched surfaces, lost time, the memory of a friend’s death, the impermanence of life. A melancholy cloud drifts over me.

If I were still teaching in the classroom, I’d have my young students sit quietly and look for the wabi sabi around them, or in their memories, and nod to each a knowing smile. I’d read them the haiku of the famous Japanese poet, and “father of the haiku form,” Matsuo Basho, and teach haiku construction—5 syllables, 7 syllables, 5 syllables. We’d talk about nature’s beauty and unfinished imperfection woven through Basho’s poetry, what it means, then dim the lights, turn on soft music, and set the children loose on the page. After, we’d gather in a circle on the rug to share our poetry in hushed tones. Between each haiku, we’d pause and breathe in and out in appreciative silence.

I pick up the picture book Wabi Sabi to read again and draw in my breath through my teeth.

A journal is splayed on the bookshelf, stained with coffee circles, half filled with story ideas, poems, haiku. Sitting in my reading chair, I open my journal, turn to a blank page and write:

The New Year begins

Hold tight to hope, love and peace

An imperfect world

References

Wabi Sabi, Reibstein Mark, illustrated by Ed Young; Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 2008.

All quotes in italics are from the book. The picture book’s back matter is worth of study.

Author Mark Reibstein and illustrator Ed Young discuss the surprising creation of their picture book, Wabi Sabi.

Youtube video, “Eastern Philosophy- Matsuo Basho,” from the video series, “School of Life.” Easily accessible to younger children, this informative video of Basho’s haiku and his influence on wabi sabi philosophy is helpful background to understanding Reibstein and Young’s picture book.

1 thought on “That Wabi Sabi Feeling”

Thanks for this post. You’ve inspired me to read that book!