“Finding Your One True Story.” That was the title of author Meg Medina’s lecture at Hamline University’s MFAC residency this January. I was in the audience, pondering her words. Finding your “one true story” implies that we all have one true story. What was mine?

Last year, 2017, was a big year for Sachiko. I had plenty of opportunities to talk about Sachiko’s story as a Nagasaki atomic bomb survivor. But 2018 is a new year and a blank slate or, to update the phrase, a blank computer screen. What is my next big writing project? If I knew my “one true story,” maybe I could answer that question.

How do we find our “one true story”? Meg Medina offered an answer. Listen. Listen to your deep internal rhythms. Meg listened to the “clave” beat of Cuban jazz and the internal thrum of her Cuban roots. Even as a child, that thrum was there, growing louder as Meg grew older. Out of Meg’s consciousness, intersecting themes emerged: culture, family, and the lives of girls. These themes became Meg’s personal “clave,” a beat to follow for writing and for living her life. To find her story, she asks the questions: Who is frightened? Who is hurt? Who loves? Who needs love? Why does all this matter? Meg digs into the crevices of her memory where remembering and forgetting are braided together. In the crevices of memory, Meg finds the way into her next story—her next big writing project.

Meg Medina is a novelist, a fiction writer. I bend toward narrative nonfiction. Where does my “one true story” lie? Several years ago, I was cleaning out a basement storage closet and found a box labeled—childhood. It was my box of forgetting and remembering. A whiff of mildew spewed out when I opened the box. I sifted through school photos, pencil sketches, notebooks of stories and heartbreaking middle school poetry, a tiny Teddy Bear, and a diary with a broken lock.

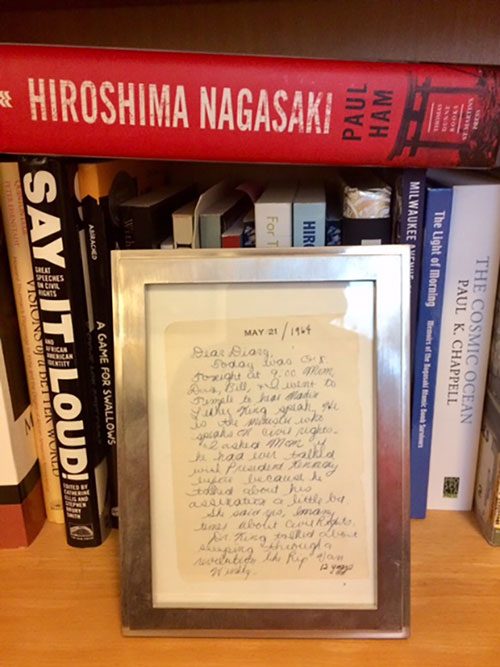

I opened the diary. A few blank yellowed pages fell to the floor. I turned the next pages with more care, smiling at my loopy cursive writing. How old was I on these pages? About twelve? I read a few entries with disappointment. Most of the entries were little more than a daily description of events. I turned a few more pages and the diary splayed open to May 21, 1964.

“Tonight at 9:00, Mom, Dad, Bill [my older brother] and I went to Temple to hear Martin Luther King speak … He is the minister that speaks on Civil Rights. I asked Mom if he had ever talked with President Kennedy … She said yes, many times … Dr. King talked about ‘sleeping through a revolution like Rip Van Winkle.’”

At twelve, I caught the line about “sleeping through a revolution like Rip Van Winkle”? Astonishing! I tore the page out of the diary and framed it to remind me of my twelve-year-old self. The framed diary page has been on my bookcase ever since. I’ve wondered how much of my memory of Martin Luther King, Jr., resonated when Sachiko Yasui told me about her own memories of King—how King’s words of love, justice, and peace, so like the words of Sachiko’s father and Mahatma Gandhi, never left her mind. During each visit with Sachiko, she would emphasize how discrimination, racism, and hate are the sparks that ignite war. Each time Sachiko spoke of discrimination, my mind traced back to my childhood days of being the only Jewish kid in my elementary school. The anti-Semitic taunts still live in my inner ear. My father’s nightmare screams from fighting through Nazi Germany still send chills through me. The more I think about writing Sachiko, the more I know I was touching my “one true story,” too.

“Sleeping through a revolution like Rip Van Winkle.” I’ve wondered about that line from my diary for a long time. Why did that line end up in my childhood diary and in my memory? While researching Sachiko, I read nearly all of Martin Luther King’s speeches. When I came across the Rip Van Winkle quote, I smiled. Good for my twelve-year-old self, I had gotten the quote right. Not long after I framed the Martin Luther King diary page, I found another quote on an old calendar: “The wonder we had as children is in our cells. We have only to listen to our memory.” I cut out the quote, and taped the paper to the back of the frame. When I read the quote now, I think of Meg Medina and her “one true story.”

Before I began this essay, I moved the framed diary page from my bookcase to my writing desk. I don’t know if this long-ago diary entry will lead me to my next big writing project or not, but I’m thinking about what’s next. This January, we celebrated Martin Luther King’s 89th birthday. The same issues King addressed—discrimination, fear and hatred of “the other”—are in the news, our politics, our neighborhood, our conversations. I hope to stay wide awake and uncover stories that speak to both our time and my twelve-year-old self. I hope the next story I write, and the one after that, and after that, have at their cores my “one true story.” Those are the stories I hope to write.

Martin Luther King Speaks! Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution. National Cathedral Washington, D.C., on 31 March 1968. (King referred to the story of Rip Van Winkle in 1958 and throughout his speeches until his death in 1968.)