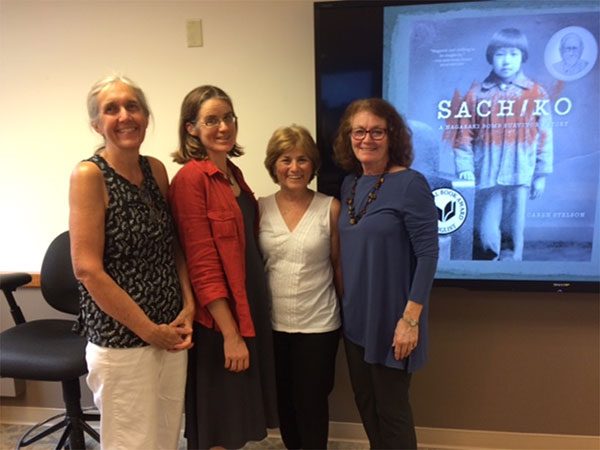

This August, I was invited to Madison, Wisconsin to share Sachiko Yasui’s story of surviving the Nagasaki atomic bomb. The Women’s International League for Peace and Justice and Physicians for Social Responsibility were my hosts. I thoroughly enjoyed speaking at Madison’s “Lanterns for Peace” event and at the Central Library, but the most surprising venue was the University of Wisconsin’s Medical School.

Dr. Monica Volmann with Physicians for Social Responsibility reached out by email. She wrote: “I was so struck by Sachiko’s story (which I read with my 11-year-old son …) and how each one of [Sachiko’s] family members showed the immediate and delayed medical effects of their nuclear exposures in a different way. It couldn’t have been better told for a “medical textbook” on the effects of radiation.”

Dr. Volmann suggested that she and I give a lecture to resident MDs at the University of Wisconsin’s Medical School about the life-threatening dangers of radiation exposure. Mary Doherty, public health advisor with Physicians for Social Responsibility and with experience on the ground at Chernobyl and Fukushima would join us. The three of us would use Sachiko and her family’s survivor experiences as medical case studies. This was a first for me. As a writer for children and young adults, I had not expected doctors as my audience.

On the afternoon of August 9—the 72nd anniversary of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki—Monica Volmann, Mary Doherty, and I stood in front of a classroom of medical doctors. In our hands was the New York Times, and on the front page was a photo of Donald Trump with his challenge to North Korea: “They will be met with fire and fury like the world has never seen.”

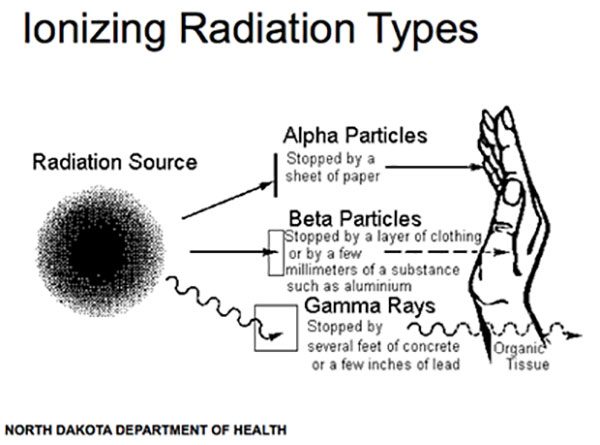

The world has already seen “fire and fury.” Towards the end of World War II, on August 6 and 9, 1945, the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki faced nuclear war. The Hiroshima atomic bomb, “Little Boy,” killed approximately 140,000 people; Nagasaki’s “Fat Man” killed 74,000—two cities destroyed by two bombs. Thousands faced immediate death, thousands more suffered life-long effects from burns, radiation exposure, and cancers. The nuclear weapons we have today are far more destructive than the first atomic bombs detonated in 1945. We asked the classroom of doctors to imagine facing a nuclear accident, or worse, nuclear war. What would they do as medical first responders?

I began by reading parts of Sachiko. Dr. Vohmann displayed her medical PowerPoint slides. It looked and sounded something like this.

“Sachiko lay in bed, hovering between life and death. She was too ill to eat, too tired to concentrate. She spiked a high fever. Her hair fell out. Her gums bled. Tiny purple spots appeared on her body, spread, and within a few days grew into dots the size of peas. Lesions opened in her skin. Flies laid eggs in them. The maggots caused itching and excruciating pain. Sachiko’s dead brothers called to her again, ‘Come with us.’”

Acute Radiation Illness

Acute Radiation Illness

Signs and Symptoms:

- • Nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, loss of appetite

- • Skin burns, petechiae

- • Weakness/Fatigue

- • Fainting

- • Inflammation of tissues

- • Mucosal bleeding

- • Anemia, longer term decrease in WBC

- • Hair loss

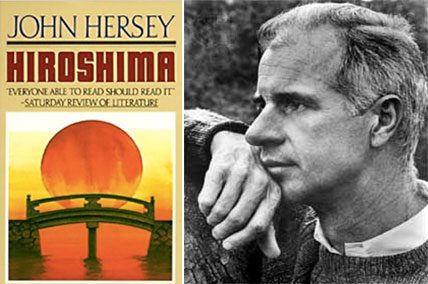

The lecture was chilling. What was more chilling for me than our lecture was my research reading hundreds of narrative accounts of people who survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My eyes have been opened. I could not walk away from writing Sachiko’s story without concluding nuclear weapons are a military absurdity of existential proportions. Author John Hersey sums up the importance of the atomic bomb survivors’ stories.

The lecture was chilling. What was more chilling for me than our lecture was my research reading hundreds of narrative accounts of people who survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki. My eyes have been opened. I could not walk away from writing Sachiko’s story without concluding nuclear weapons are a military absurdity of existential proportions. Author John Hersey sums up the importance of the atomic bomb survivors’ stories.

“What has kept the world safe from the bomb since 1945 has not been deterrence in the sense of fear of specific weapons, so much as it’s been memory, the memory of what happened at Hiroshima.“

Today the world has about 15,000 nuclear weapons, 90% owned by the United States and Russia. In January 2017, with concerns for nuclear warfare, climate change, and the election of Donald Trump, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists moved the hands on the Doomsday Clock from 3 minutes to midnight to 2 ½ minutes. None of us can be complacent.

What can we do? We can find the time and courage to work for peace no matter how we define our paths. No one can know the ripple effects of our smallest steps. If anyone had asked me five years ago if I would be speaking to a room full of doctors about radiation exposure, nuclear war, and the critical importance of world peace, I would have shaken my head no, “Not me.”

Five years ago, I may not have understood this either: We have no idea how powerful our books for children and young adults can be, what audiences they may inspire, and how much good our stories can do out in the world. Books for children and young adults are books for us all.

Resources

Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

Physicians for Social Responsibility, Wisconsin: